SDriver: Location-Specific Signatures

Prevent SQL Injection Attacks

Dimitris Mitropoulos and Diomidis Spinellis

Department of Management Science and Technology

Athens University of Economics and Business

{dimitro,dds}@aueb.gr

Abstract

SQL injection attacks involve the construction of application

input data that will result in the execution of malicious SQL

statements.

Many web applications are prone to SQL injection

attacks.

This paper proposes a novel method for preventing this kind

of attacks by placing a database driver proxy between the application and

its underlying relational database management system.

To detect an attack, the driver uses stripped-down SQL queries and

stack traces to create SQL statement signatures that are then

used to distinguish between injected and legitimate queries.

The driver depends neither on the application nor on the RDBMS

and can be easily retrofitted to any system.

We have developed a tool, SDriver, that

implements our technique and tested it successfully on several web applications.

1 Introduction

Traditionally, most programmers have been trained in terms of writing

code that implements the required functionality without considering

its many security aspects [16].

It is very common, for a programmer, to make false assumptions about

user input [28].

Classic examples include: assuming only numeric characters will be entered

as input, or that the input will never exceed a certain length.

SQL injection attacks comprise a subset of a wide set of attacks

known as code injection attacks [18,2].

Code injection is a technique to introduce code into a computer program or

system by taking advantage of the unchecked assumptions the system makes about

its inputs [31].

Many web applications have interfaces where a user can input data

to interact with the application's underlying relational database management

system RDBMS.

This input becomes part of an SQL statement, which is then executed

on the RDBMS.

A code injection attack that exploits the vulnerabilities of

these interfaces is called an " SQL injection attack" ( SQLIA)

[6,25,16,27].

There are many forms of SQL injection attacks. The

most common involve taking advantage of:

- incorrectly passed parameters,

- incorrectly filtered quotation characters, or

- incorrect type handling.

With this kind of attacks, a malicious user can view sensitive

information, destroy or modify protected data, or even crash the entire

application [1].

Consider a trivial example that takes advantage of incorrectly

filtered quotation characters.

In a login page, besides the user name and

password input fields, there is usually a separate field where users

can input their e-mail address, in case they forget their password.

The statement that is probably executed can have the following form:

SELECT * FROM passwords WHERE email =

'theemailIgave@example.com';

If an attacker, inputs the string anything' OR 'x'='x, she could

conceivably view every item in the table.

In a similar way, the attacker could modify the database's contents or schema.

An "incorrect type handling" attack occurs when a user-supplied

field is not strongly typed or is not checked for type constraints.

For example, many websites allow users, to access their older press releases.

A URL for accessing the site's fifth press release could look like this

[24]:

http://www.website.com/pressRelease.jsp?RelID=5

And the statement that is probably executed is:

SELECT description, issuedate, body FROM pressRel WHERE RelID = 5

If some attackers wished to find out if the application is vulnerable to SQL injection,

they could change the URL into something like:

http://www.website.com/pressRelease.jsp?pressReleaseID=5%20AND%201=1

If the page displayed is the same page as before, it is clear that

the field RelID is not strongly typed and end users can manipulate the

statement as they choose.

Note that, while the first attack could be countered by filtering out

the quotation characters from the input data, countering the second

attack would require code to ensure that the input data is a single

integer.

According to vulnerability databases like CVE (Common

Vulnerabilities and Exposures)1

SQLIA incidents have increased significantly over the last years.

2 Countering SQL Injection Attacks

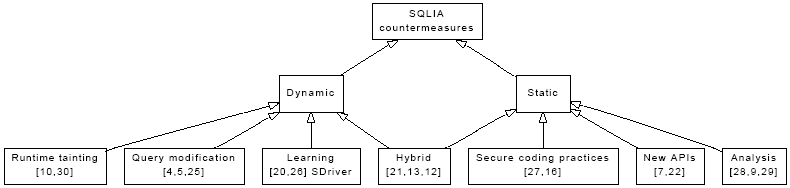

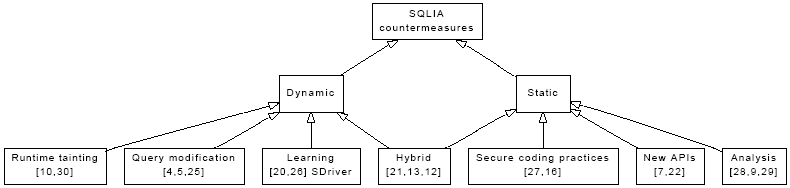

Figure 1:

A taxonomy of SQLIA countermeasures

A taxonomy of SQLIA countermeasures appears in Figure 1.

Static approaches detect or counteract the possibility of an SQLIA

at compile time, while dynamic approaches perform this task at runtime.

Note that both approaches may require the analysis or modification

of an application's source code.

On the static front an often repeated mantra is the adoption

of secure coding practices [27,16].

Most SQL injection attacks can be prevented by passing user data

as parameters of previously prepared SQL statements instead of

intermingling user data directly in the SQL statement.

For example, the statement we examined previously, could be passed to

the database with a question mark used as a placeholder for the parameter,

and a separate type-checked API call could be used for setting the

first parameter of the SQL statement to the desired value.

In Java, this would be accomplished by the following method calls.

PreparedStatement pstmt = con.prepareStatement(

"SELECT description, issuedate, body FROM pressRel" +

"WHERE RelID = ?");

pstmt.setInt(1, 5);

These practices can indeed increase the robustness of applications.

However, experience has shown us that the expectation

for them to be embraced to the extent of completely eliminating

security vulnerabilities is just wishful thinking.

An alternative approach involves the introduction of

type-safe programming interfaces, like DOM SQL [22] and the

Safe Query Objects [7].

Both eliminate the incestuous relationship between untyped

Java strings and SQL statements, but don't address

legacy code, while also requiring programmers to learn

a radically new API.

An approach that deals with existing code and coding practices

involves the static analysis of the application's source code

to locate SQL statement invocations that are considered

unsafe [28,9,29].

While the impact of tools based on these methods on

development and deployment processes is minimal,

their accuracy and scope is reduced by the complexity

of modern web-based application frameworks.

For instance, recent work by Wassermann and Su [29]

proposes a sound and precise approach, which however

depends on specifying the semantincs of all PHP

string functions.

(The implementation described contains specifications for 243 functions.)

On the dynamic front runtime tainting approaches enforce security policies by

marking untrusted data and tracing its flow through the program.

For instance the system by Xu et al. [10] covers applications

whose source code or their interpreter is written in C,

while the work by Haldar et al. [30] targets Java code.

These approaches generally require significant changes to a

language's compiler or its runtime system.

Another dynamic approach involves query modification.

Here the modified query is either reconstructed at runtime using

a cryptographic key that is inaccessible to the attacker [4],

or the user input is tagged with delimiters that allow an augmented

SQL grammar to detect SQLIAs [5,25].

Both approaches require significant source code modifications.

Training approaches are based on the ideas of Denning's

original intrusion detection framework [8]:

they record and store valid SQL statements and thereby

detect SQLIAs as outliers from the set of valid statements.

An early approach, DIDAFIT [20] recorded all database

transactions.

Subsequent refinements tagged each transaction with the

corresponding application [26].

Our system further improves on these techniques by

automatically determining precisely each query's location through its

stack trace.

Finally, some approaches combine a static analysis with runtime

monitoring.

For instance, AMNESIA, associates a query model with

the location of each query in the application and then

monitors the application to detect when queries diverge from

the expected model [13,12].

A more general hybrid approach involves the location of

SQLIAs using the program query language PQL [21].

The PQL queries are evaluated through both

a static analysis and the dynamic monitoring

of instrumented code.

These approaches, although complex to implement,

seem to offer an additional margin of protection against

false positives and negatives.

Readers looking for a more detailed survey

of SQL injection attacks and the corresponding

countermeasures can turn to the recently published survey

by Halfond and his colleagues [14].

In this paper we propose a novel technique of preventing SQLIAs.

Our technique incorporates a driver that stands between the web front-end

and the back-end database.

The key property of this driver is that every SQL statement can be

identified using the query's location and a stripped-down version

of its contents.

By analyzing these characteristics during a training phase, we can

build a model of the

legitimate queries.2

Then at runtime our driver

checks all queries for compliance with the trained model and can thus

block queries containing additional maliciously injected elements.

The work reported here builds upon an earlier prototype [23]

with a more robust SQL processing technique, significant performance

improvements, and more extensive validation experiments.

Figure 1:

A taxonomy of SQLIA countermeasures

A taxonomy of SQLIA countermeasures appears in Figure 1.

Static approaches detect or counteract the possibility of an SQLIA

at compile time, while dynamic approaches perform this task at runtime.

Note that both approaches may require the analysis or modification

of an application's source code.

On the static front an often repeated mantra is the adoption

of secure coding practices [27,16].

Most SQL injection attacks can be prevented by passing user data

as parameters of previously prepared SQL statements instead of

intermingling user data directly in the SQL statement.

For example, the statement we examined previously, could be passed to

the database with a question mark used as a placeholder for the parameter,

and a separate type-checked API call could be used for setting the

first parameter of the SQL statement to the desired value.

In Java, this would be accomplished by the following method calls.

PreparedStatement pstmt = con.prepareStatement(

"SELECT description, issuedate, body FROM pressRel" +

"WHERE RelID = ?");

pstmt.setInt(1, 5);

These practices can indeed increase the robustness of applications.

However, experience has shown us that the expectation

for them to be embraced to the extent of completely eliminating

security vulnerabilities is just wishful thinking.

An alternative approach involves the introduction of

type-safe programming interfaces, like DOM SQL [22] and the

Safe Query Objects [7].

Both eliminate the incestuous relationship between untyped

Java strings and SQL statements, but don't address

legacy code, while also requiring programmers to learn

a radically new API.

An approach that deals with existing code and coding practices

involves the static analysis of the application's source code

to locate SQL statement invocations that are considered

unsafe [28,9,29].

While the impact of tools based on these methods on

development and deployment processes is minimal,

their accuracy and scope is reduced by the complexity

of modern web-based application frameworks.

For instance, recent work by Wassermann and Su [29]

proposes a sound and precise approach, which however

depends on specifying the semantincs of all PHP

string functions.

(The implementation described contains specifications for 243 functions.)

On the dynamic front runtime tainting approaches enforce security policies by

marking untrusted data and tracing its flow through the program.

For instance the system by Xu et al. [10] covers applications

whose source code or their interpreter is written in C,

while the work by Haldar et al. [30] targets Java code.

These approaches generally require significant changes to a

language's compiler or its runtime system.

Another dynamic approach involves query modification.

Here the modified query is either reconstructed at runtime using

a cryptographic key that is inaccessible to the attacker [4],

or the user input is tagged with delimiters that allow an augmented

SQL grammar to detect SQLIAs [5,25].

Both approaches require significant source code modifications.

Training approaches are based on the ideas of Denning's

original intrusion detection framework [8]:

they record and store valid SQL statements and thereby

detect SQLIAs as outliers from the set of valid statements.

An early approach, DIDAFIT [20] recorded all database

transactions.

Subsequent refinements tagged each transaction with the

corresponding application [26].

Our system further improves on these techniques by

automatically determining precisely each query's location through its

stack trace.

Finally, some approaches combine a static analysis with runtime

monitoring.

For instance, AMNESIA, associates a query model with

the location of each query in the application and then

monitors the application to detect when queries diverge from

the expected model [13,12].

A more general hybrid approach involves the location of

SQLIAs using the program query language PQL [21].

The PQL queries are evaluated through both

a static analysis and the dynamic monitoring

of instrumented code.

These approaches, although complex to implement,

seem to offer an additional margin of protection against

false positives and negatives.

Readers looking for a more detailed survey

of SQL injection attacks and the corresponding

countermeasures can turn to the recently published survey

by Halfond and his colleagues [14].

In this paper we propose a novel technique of preventing SQLIAs.

Our technique incorporates a driver that stands between the web front-end

and the back-end database.

The key property of this driver is that every SQL statement can be

identified using the query's location and a stripped-down version

of its contents.

By analyzing these characteristics during a training phase, we can

build a model of the

legitimate queries.2

Then at runtime our driver

checks all queries for compliance with the trained model and can thus

block queries containing additional maliciously injected elements.

The work reported here builds upon an earlier prototype [23]

with a more robust SQL processing technique, significant performance

improvements, and more extensive validation experiments.

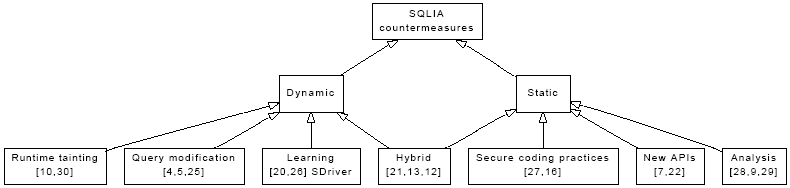

3 A Signature-Based Proxy Driver

The architecture of typical tiered web applications consists of at

least an application running on a web server and a back-end database

[28].

Between these two tiers, there is in most cases a database

connectivity driver based on protocols like ODBC (Open

Database Connectivity) or JDBC (Java Database Connectivity).

The main function of such a driver is to provide a portability layer by

obtaining SQL statements from the application and forwarding them

to the database.

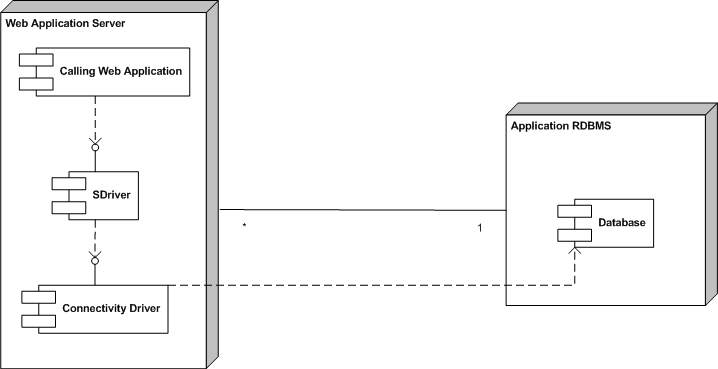

The driver that we propose is also a connectivity

driver that operates however as a shim or proxy

standing between the application and the database interface driver

(see Figure 2).

Our driver is transparent: its only role is to

prevent SQLIA, and it depends neither on the application, nor on

the underlying connectivity driver.

Figure 2:

The architecture of our proposed driver

To work as a connectivity driver, our driver implements the complete

interface of the connectivity protocol.

However, most of the driver's methods simply forward the request to the

underlying connectivity driver.

Only a few methods capture and process requests in order to

prevent SQLIAs.

In this respect our driver acts as a proxy for the underlying driver

working as a firewall between the original driver and the application.

In order to secure the application from SQLIAs the driver must

go through a training phase.

This involves executing all the SQL queries of the application

so that the driver can identify them in a way we will show

in the next section.

Then, the driver's operation can shift into production mode, where the

driver takes into account all the trained legitimate queries to

prevent SQLIAs by detecting and blocking them.

Figure 2:

The architecture of our proposed driver

To work as a connectivity driver, our driver implements the complete

interface of the connectivity protocol.

However, most of the driver's methods simply forward the request to the

underlying connectivity driver.

Only a few methods capture and process requests in order to

prevent SQLIAs.

In this respect our driver acts as a proxy for the underlying driver

working as a firewall between the original driver and the application.

In order to secure the application from SQLIAs the driver must

go through a training phase.

This involves executing all the SQL queries of the application

so that the driver can identify them in a way we will show

in the next section.

Then, the driver's operation can shift into production mode, where the

driver takes into account all the trained legitimate queries to

prevent SQLIAs by detecting and blocking them.

3.1 Training Mode

Every SQL query of an application is identified through a signature

created by combining three of its characteristics.

- The method invocation stack trace.

This includes the details of all methods and call location, from

the method of the application where the query is executed down to the

target method of the connectivity driver.

- The SQL keywords.

- The tables and the fields that the query uses in order to retrieve

its results.

By combining all the fixed elements of each query

with its invocation method's stack trace,

we obtain a unique identifier-signature-for all the legitimate

queries of an application.

A formal representation of the application's signatures that should

be accepted as legitimate is the following:

If during an application's normal (non-attacked) run,

K is the set of method stack traces at the point where an SQL

statement is executed;

L is the set of the corresponding SQL keyword names;

M the set of the corresponding database table names,

and N the set of the corresponding table field names,

the set of the legitimate query signatures S is defined as follows:

|

S = { ω: ω = (k, a1, a2, ...), k ∈ K, ai ∈ (L ∪M ∪N ) } |

| (1) |

When the system operates in the training mode, each query

signature Q is added to S.

In production mode a query with a signature Q is considered

legal iff Q ∈ S.

Obviously, a query cannot be unambiguously identified by using just one of the

above characteristics, such as the query's keywords,

and this is why all of them are combined into a tuple.

To combine these characteristics, when a query is being sent to the database

our driver carries out two actions.

First, it strips down the query, removing all numbers and string literals.

So if the following statement is being executed

SELECT table1.field1 FROM table1 WHERE table1.field2 = 'foo' AND

table1.field3 > 3

the driver removes 'foo' and 3 from the query string.

The driver also traverses down the call stack, saving the details of each

method invocation, until it reaches the statement's origins.

The association of stack frame data with each SQL query-a process that

to the best of our knowledge is unique to our approach-is an important

defense against maliciously crafted attacks that try to masquerade

as legitimate queries.

As an example, consider an application that will send the password

for a forgetful user, Alice, via email by executing

SELECT password from userdata WHERE id = 'Alice'

This same application could allow users to lock their terminal,

but allow the unlocking either with the user's password or with

the administrator password (the 4.3 BSD lock command

behaved in this peculiar way).

The corresponding query to verify the password on the locked

Alice's workstation would be as follows.

SELECT password from userdata WHERE id = 'Alice' OR id = 'admin'

It is now easy to see that a malicious user, Bob, could obtain the

administrator's password by email by entering on the password retrieval form

as his user identifier

nosuchuser' OR id = 'admin

Without the differentiating factor of a stack trace,

the preceding query would have the same signature as the one used for

unlocking the terminal, and would therefore escape a traditional

signature-based SQLIA protection system.

Our initial design had SDriver storing each query's keywords,

table names, and stack trace into separate tables of an auxiliary database.

During implementation we realized that, because the only operations we

were interested in were adding a query Q to the set of known queries S

and testing whether Q ∈ S, we could substitute the full signature S with

its hash.

This substitution is valid, because SDriver operates under the premise

of best effort rather than absolute correctness [15].

Therefore, the stack trace and the stripped down query are concatenated and

the driver applies a hash function on them to form the stored form

of the query signature.

When the system is operating in training mode, all the signatures are saved

in an auxiliary database table, so that when the system operates in production

mode the driver can check whether a query is legitimate or not.

This is done off-line

since an on-line training could lead to disputable signatures.

Specifically, if an attack is

attempted the generated signature is going to be stored as a legitimate one

putting the system's operation at risk.

3.2 Production Mode

The driver's functionality during the production mode does not differ

significantly from the one in the training mode.

The steps are the same until the driver derives the query's signature.

At that point, the driver consults the database table of saved query

signatures to verify that the query is legal.

This interaction though, happens in an indirect way as we describe

in Section 5.2.

If the driver identifies it as a legitimate one then the query passes through.

If it does not, then the application is probably under attack.

In such a case the driver can halt the application with an exception, it

can log an error message, or it can forward an alarm to an enterprise-wide

intrusion detection system.

As an example, consider an attack that takes advantage of incorrectly

filtered quotation characters.

The additional keywords that the malicious user injects will definitely

lead to an unknown signature. In this case the driver becomes aware of

the attack and prevents it.

4 Java Platform Implementation

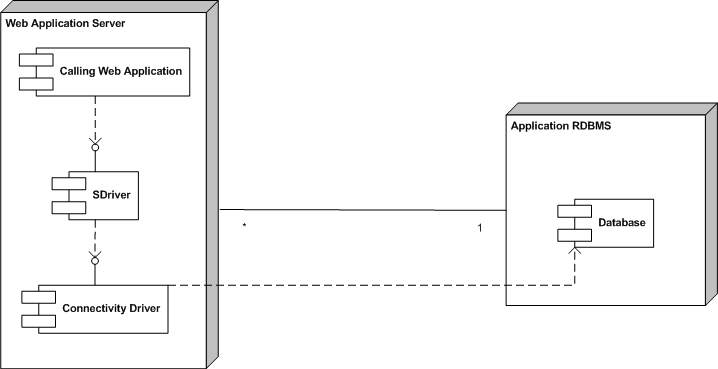

Figure 3:

SDriver's architecture

We have implemented our solution in the Java platform, but implementations

in other operating environments are certainly feasible.

The secure database driver, which we call SDriver, acts as a JDBC

driver wrapped around other drivers that implement a database's

JDBC protocol (see Figure 3).

Figure 3:

SDriver's architecture

We have implemented our solution in the Java platform, but implementations

in other operating environments are certainly feasible.

The secure database driver, which we call SDriver, acts as a JDBC

driver wrapped around other drivers that implement a database's

JDBC protocol (see Figure 3).

4.1 Proxy Interface

JDBC drivers known as "native-protocol drivers"3

(or type 4 JDBC drivers) convert JDBC calls directly into

the vendor-specific database protocol.

At the client's (application) side, a separate driver is needed for each database.

SDriver does not depend on the application or the native driver and it

is placed between them.

To accomplish that, the application must be modified in a single position:

in the location where the application establishes a

connection with a driver.

For the application to be secured, the SDriver must establish a connection

with the driver that the application is meant to use.

To achieve that, we pass the driver's name through the URL of the

original connection (see Figure 3).

For example, if the application is meant to connect to

the Microsoft SQL Server 2000 the source code would look like this:

Class.forName ("com.microsoft.jdbc.sqlserver.SQLServerDriver");

Connection conn=DriverManager.getConnection(

"jdbc:microsoft:sqlserver://localhost:1433;databasename=MyDB",

üsername", "password");

The modified code for using the SDriver would be:

Class.forName (örg.SDriver");

Connection conn = DriverManager.getConnection(

"jdbc:com.microsoft.jdbc.sqlserver.SQLServerDriver:" +

"microsoft:sqlserver://localhost:1433;databasename = MyDB",

üsername", "password");

4.2 Implementation Details

manageQuery(String query)

signature = getQuerySignature(stripQuery(query));

if (inSignatureTable(signature))

return;

if (inTrainingMode)

// insert signature into the signature table

else

// issue an alarm or raise an exception

// write query to a log file

stripQuery(String query)

query = removeQuotedStrings(query);

query = removeNumbers(query);

query = removeComments(query);

getQuerySignature(String query)

for (StackTraceElement ste : stackTrace)

signature.append(ste);

signature.append(query);

return MD5(signature);

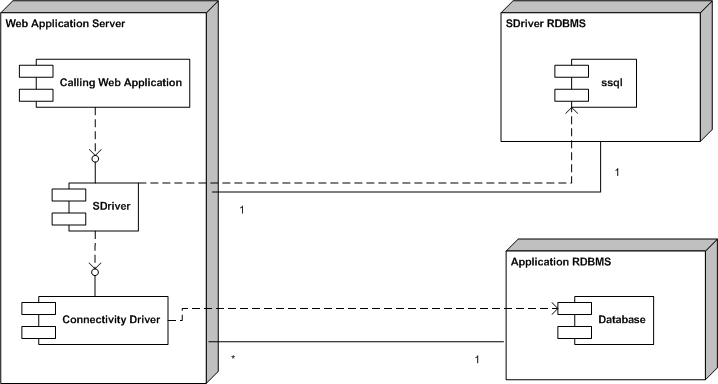

Figure 4:

The operation of SDriver

SDriver is not a classic native-protocol RDBMS driver.

The implementation of most of the driver's methods simply involves calling the

corresponding methods of the underlying driver.

Only a few methods from those that a native-protocol driver implements

pass SQL code through them, and can therefore be used to launch an SQLIA.

These methods are the various forms of

addBatch,

execute,

executeQuery, and

executeUpdate.

To secure applications against SQLIAs,

SDriver interposes itself in these methods examining

the query string that is about to be executed.

For this examination to take place, SDriver follows the steps of

the pseudocode listed in Figure 4.

Figure 3 shows that SDriver depends on

another database component called ssql.

This works as the signature data store.

One of the tricky parts of the SDriver implementation is the code that

traverses the application's stack.

Perversely, in Java the way to access the stack frames is to

create an object of type Throwable.

The class Throwable is the superclass of all errors and

exceptions in Java.

To aid the display and debugging of exceptions Throwable

objects support a method called getStackTrace, which returns

an array of stack frames.

Each stack frame provides methods for obtaining the corresponding

file name, method name, and line number.

The following listing shows the contents of a stored stack trace:

com.SStatement.getQuerySignature(SStatement.java:556)

com.SStatement.manageQuery(SStatement.java:489)

com.SStatement.executeQuery(SStatement.java:430)

beans.querybean.selection1(querybean.java:20)...

Every stack element contains information about a method invocation

including the method name, the package, the file, and the line number.

The first method will always be getQuerySignature

because it is the one that traverses the call stack.

The element that participates more in the diversity of a signature

is typically the fourth one: the application's method that directs the connectivity

driver to pass the query to the database.

5 Evaluation

The success of any system claiming to improve security typically

depends on the accuracy of its results (often measured in terms of

false positives and negatives) and on its cost in terms of deployment,

operation, and maintenance.

5.1 Accuracy

We evaluated the accuracy of SDriver through three experiments:

a synthetic benchmark,

a notoriously insecure application, and

a bundle of previously evaluated real-world applications.

Our synthetic benchmark was a JSP application with the same technical

characteristics as those described in reference [4].

This application allowed a user to inject SQL into a "where" clause

with no input validation, and retrieve information concerning

application data.

After placing SDriver between the application and the database,

the attack was successfully prevented.

We then searched for a real-world web application that had a record

of being vulnerable to SQLIAs.

According to the common vulnerability database CVE and the

security bulletin providers

US-CERT,4

Secunia,5

and Armorize Technologies,6

a notoriously vulnerable application is Daffodil CRM

1.5.7

In Daffodil 1.5, remote attackers could execute arbitrary SQL

commands via unspecified parameters in a login action.

In particular, users wanting to access Daffodil had to fill-in a simple

username and password form. By using a SQLIA similar to the one

we presented in Section 1, an unauthorized user could

access administrator facilities. SDriver recognized and

blocked the attack, without otherwise interfering with Daffodil's operation.

Finally, we selected five real-world web

applications that have been used in the literature

for previous evaluations 8 [11,25].

We attempted a wide variety of attacks based on incorrectly filtered

quotation characters, incorrectly passed parameters, untyped parameters,

tautologies, and others [1,14].

Table 1 shows, for each web application, the number

of the signatures stored in the SDriver database after training,

the number of unsuccessful attacks (attacks that did not get past

the application's defenses), the number of successful attacks

(attacks that could potentially compromise the application), and

the number of attacks prevented by SDriver, in absolute terms

and as a percentage over the total number of successful attacks.

The table's columns follow the labeling introduced in reference [11].

| Application | Signatures | Unsuccessful | Successful | Prevented |

| synthetic benchmark | 21 | 55 | 29 | 29 (100%) |

| daffodil | 72 | 77 | 27 | 27 (100%) |

| bookstore | 168 | 288 | 39 | 39 (100%) |

| classifieds | 122 | 270 | 37 | 37 (100%) |

| employee directory | 61 | 207 | 31 | 31 (100%) |

| events | 65 | 115 | 29 | 29 (100%) |

| portal | 156 | 312 | 49 | 49 (100%) |

Table 1:

SDriver's Precision

While testing, we realized that the five previously evaluated applications

shared a common feature:

in a misguided attempt to avoid SQLIAs, they scanned user input for

single quotation marks and replaced them with double quotation marks.

This technique masked the SQLIA problem, but introduced

a data leakage vulnerability.

For instance, a user input parameter consisting of the

string any\' in the application "portal"

would result in the execution of the following query:

SELECT e.date_start AS e_date_start, e.event_desc AS e_event_desc,

e.event_name AS e_event_name, e.location AS e_location,

e.presenter AS e_presenter FROM events e WHERE

(e.event_desc LIKE ' e.presenter LIKE '

The preceding statement would raise an exception revealing information

about the underlying database and its schema.

Given that our driver works as a wrapper around other

connectivity drivers, we could also instrument it

to handle exceptions when running in production mode.

As a result, critical information like the above would not be revealed.

However, because

well-written applications have their own sophisticated exception handling,

we made secure exception handling an optional configurable

feature.

With its secure exception handling activated, our tool successfully

prevented all SQLIAs in this last test without suffering from

false negatives.

Furthermore,

we did not encounter false positives (legitimate queries misreported as

an attack) in any of the three experiment classes we performed.

5.2 Operation Cost

| Application | Execution time (ns) | |

| Database | Original | SDriver | Overhead (%) |

| SQL Server | 175 | 183 | 4.7 |

| My SQL | 121 | 126 | 3.7 |

Table 2:

Proxy driver baseline cost

| Application | Execution time (μs) | Overhead (%) |

| Database | Original | Training | Production | Training | Production |

| SQL Server | 605 | 1221 | 841 | 102 | 39 |

| My SQL | 401 | 1009 | 613 | 60 | 35 |

Table 3:

The cost of SQL query processing under SDdriver

The acquisition cost of SDriver is minimal,

because we are releasing it as open-source software.9

Deploying SDriver is also relatively straightforward:

the only requirement is the ability

to modify the database's connection string.

This can be achieved by specifying an appropriate application-specific

parameter (Java property), by modifying the source code, or (in extreme cases)

by patching the application's binary.

Furthermore, one must then execute the application in training mode.

An automated test suite that will exercise (ideally all) the application's calls

to methods containing SQL strings with user-input data, would make

this exercise trivial.

Otherwise appropriate scenarios must be devised and executed each

time a new version of the application is installed.

The driver's architecture allowed us to test its performance

on two RDBMSs:

SQL Server 2000 and My SQL (version 5.0.24).

All tests were performed on a

Pentium 4 CPU clocked at 2.6 GHz on a machine with 512 MB RAM

running Java 1.6.0 under Windows XP Professional.

We first measured the baseline overhead of SDriver by executing

a JDBC method-!getAutoCommit()!-that is passed through

directly to the underlying database driver without further processing.

The results, appearing in Table 2 indicate that the cost

of interposing SDriver is negligible.

Subsequently, we measured the overhead of the SQLIA detection code

by executing the following moderately complex SQL statement, with and

without SDriver.

SELECT d_name, d_SorL, d_year,d_genre, d_cover FROM artists,

disks, recorded WHERE a_name = '"+ selectedartist +'' AND

d_name = rec_d_name AND rec_a_name = a_name

The performance overhead for the two RDBMSs was

similar (see Table 3).

In training mode the queries take twice as long to execute.

However, this cost is not unreasonable, because this is an

execution mode that will be rarely exercised.

In production mode, the operation cost is significantly lower:

below 50% for both RDBMSs.

Early versions of our tool, incurred a significant overhead

(with a range from 239% to 279% in both training and production mode).

We optimized away this overhead by streamlining the regular

expressions used for stripping the SQL queries, and

by caching the signatures into

a static Hashtable when a connection between

the application and the SDriver is first set up in production mode.

We also considered limiting the depth of the stack frame processing

during production mode,

by calculating in training mode

a stack frame prefix tree (trie) [19,481-490],

but the performance improvements were negligible.

6 Conclusions

SDriver is a mechanism and a prototype application that prevents

SQLIAs against web applications.

If an SQL injection happens, the structure of the query, and

therefore its signature will be altered,

and SDriver will be able to detect it.

By associating a complete stack trace with the root of each query,

SDriver can correlate queries with their call sites.

This increases the specificity of the stored query signatures and

avoids false negative results.

The increased specificity of the signatures also allows us to discard

a large number of the query's elements, thereby also reducing false

positive results. A disadvantage of our approach is that when the

application is altered, the new source code structure invalidates

existing query signatures.

This necessitates a new training phase.

However, with the increased adoption of test-driven development [17],

and use of automated testing frameworks,

like JUnit [3], this training phase can often become part

of the application's testing.

The main contribution of our approach is the association of complete stack

traces with each query.

Although we have implemented SDriver as a JDBC proxy, the

same approach could also be used for applications written in other

languages, like C and C++.

Furthermore, the association of queries with their stack trace can be

used to minimize the extent of source code modification in

other approaches, like AMNESIA [13,12].

Future work on our system involves packaging it in a way that will allow

its straightforward deployment, and experimentation with different

approaches for handling the reported attacks.

References

- [1]

-

C. Anley.

Advanced SQL Injection in SQL Server Applications.

Next Generation Security Software Ltd., 2002.

- [2]

-

E. Barrantes, D. Ackley, S. Forrest, T. Palmer, D. Stefanovic, and D. Zovi.

Randomized instruction set emulation to disrupt binary code injection

attacks.

In CCS 2003: Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Computer

and Communications Security, pages 281-289, October 2003.

- [3]

-

Kent Beck and Erich Gamma.

Test infected: Programmers love writing tests.

Java Report, 3(7):37-50, July 1998.

- [4]

-

S. Boyd and A. Keromytis.

SQLrand: Preventing SQL injection attacks.

In M. Jakobsson, M. Yung, and J. Zhou, editors, Proceedings of

the 2nd Applied Cryptography and Network Security (ACNS) Conference, pages

292-304. Springer-Verlag, 2004.

Lecture Notes in Computer Science Volume 3089.

- [5]

-

G. Buehrer, B.W. Weide, and P.A. Sivilotti.

Using parse tree validation to prevent SQL injection attacks.

In Proceedings of the 5th international Workshop on Software

Engineering and Middleware, pages 106–-113. ACM Press, September 2005.

- [6]

-

CERT.

CERT vulnerability note VU282403.

Online http://www.kb.cert.org/vuls/id/282403, 2002.

Accessed, January 7th, 2007.

- [7]

-

W.R. Cook and S. Rai.

Safe query objects: statically typed objects as remotely executable

queries.

In ICSE 2005: 27th International Conference on Software

Engineering, pages 97-106, 2005.

- [8]

-

Dorothy Elizabeth Robling Denning.

An intrusion detection model.

IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 13(2):222-232,

February 1987.

- [9]

-

Carl Gould, Zhendong Su, and Premkumar Devanbu.

Static checking of dynamically generated queries in database

applications.

In ICSE '04: Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on

Software Engineering, pages 645-654, Washington, DC, USA, 2004. IEEE

Computer Society.

- [10]

-

Vivek Haldar, Deepak Chandra, and Michael Franz.

Dynamic taint propagation for Java.

In ACSAC '05: Proceedings of the 21st Annual Computer Security

Applications Conference, pages 303-311, Washington, DC, USA, 2005. IEEE

Computer Society.

- [11]

-

W. G. Halfond and A. Orso.

AMNESIA: analysis and monitoring for neutralizing SQL-injection

attacks.

In Proceedings of the 20th IEEE/ACM international Conference on

Automated Software Engineering, pages 174–-183. ACM Press, November 2005.

- [12]

-

W. G. Halfond and A. Orso.

Preventing SQL injection attacks using AMNESIA.

In ICSE 2006: Proceedings of the 28th International Conference

on Software Engineering, pages 795–-798. ACM Press, May 2006.

- [13]

-

William G. J. Halfond and Alessandro Orso.

Combining static analysis and runtime monitoring to counter

SQL-injection attacks.

In WODA '05: Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on

Dynamic Analysis, pages 1-7, New York, NY, USA, 2005. ACM Press.

- [14]

-

William G.J. Halfond, Jeremy Viegas, and Alessandro Orso.

A classification of SQL-injection attacks and countermeasures.

In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Secure Software

Engineering, March 2006.

- [15]

-

Val Henson.

An analysis of compare-by-hash.

In Proceedings of HotOS IX: The 9th Workshop on Hot Topics in

Operating Systems, pages 13-18, Berkeley, CA, May 2003. USENIX Association.

- [16]

-

Michael Howard and David LeBlanc.

Writing Secure Code.

Microsoft Press, Redmond, WA, second edition, 2003.

- [17]

-

Ron Jeffries and Grigori Melnik.

Guest editors' introduction: TDD-the art of fearless programming.

IEEE Software, 24(3):24-30, May 2007.

- [18]

-

G. S. Kc, A. D. Keromytis, and V. Prevelakis.

Countering code-injection attacks with instruction-set randomization.

In CCS 2003: Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Computer

and Communications Security, pages 272–-280. ACM Press, October 2003.

- [19]

-

Donald E. Knuth.

The Art of Computer Programming, volume 3: Sorting and

Searching.

Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, 1973.

- [20]

-

Sin Yeung Lee, Wai Lup Low, and Pei Yuen Wong.

Learning fingerprints for a database intrusion detection system.

In Dieter Gollmann, Günter Karjoth, and Michael Waidner, editors,

ESORICS '02: Proceedings of the 7th European Symposium on Research in

Computer Security, pages 264-280, London, UK, 2002. Springer-Verlag.

Lecture Notes In Computer Science 2502.

- [21]

-

Michael Martin, Benjamin Livshits, and Monica S. Lam.

Finding application errors and security flaws using PQL: a program

query language.

In OOPSLA '05: Proceedings of the 20th Annual ACM SIGPLAN

Conference on Object Oriented Programming, Systems, Languages, and

Applications, pages 365-383, New York, NY, USA, 2005. ACM Press.

- [22]

-

Russell A. McClure and Ingolf H. Krüger.

SQL DOM: Compile time checking of dynamic SQL statements.

In ICSE '05: Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on

Software Engineering, pages 88-96, 2005.

- [23]

-

Dimitris Mitropoulos and Diomidis Spinellis.

Countering SQL injection attacks with a database driver.

In Theodore S. Papatheodorou, Dimitris N. Christodoulakis, and

Nikitas N. Karanikolas, editors, Current Trends in Informatics: 11th

Panhellenic Conference on Informatics, PCI 2007, volume B, pages 105-115,

Athens, May 2007. New Technologies Publications.

- [24]

-

K. Spett.

Blind SQL injection.

Online

http://www.spidynamics.com/whitepapers/Blind_SQLInjection.pdf, 2004.

Accessed, January 7th, 2007.

- [25]

-

Zhendong Su and Gary Wassermann.

The essence of command injection attacks in web applications.

In Conference Record of the 33rd ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT Symposium on

Principles of Programming Languages POPL '06, pages 372–-382. ACM Press,

January 2006.

- [26]

-

Fredrik Valeur, Darren Mutz, and Giovanni Vigna.

A learning-based approach to the detection of SQL attacks.

In Klaus Julisch and Christopher Kruegel, editors, Intrusion and

Malware Detection and Vulnerability Assessment: Second International

Conference, DIMVA 2005, pages 123-140, July 2005.

Lecture Notes in Computer Science 3548.

- [27]

-

John Viega and Gary McGraw.

Building Secure Software: How to Avoid Security Problems the

Right Way.

Addison-Wesley, Boston, MA, 2001.

- [28]

-

Gary Wassermann and Zhendong Su.

An analysis framework for security in web applications.

In SAVCBS 2004: Proceedings of the FSE Workshop on Specification

and Verification of Component-Based Systems, pages 70-78, 2004.

- [29]

-

Gary Wassermann and Zhendong Su.

Sound and precise analysis of web applications for injection

vulnerabilities.

In PLDI '07: Proceedings of the 2007 ACM SIGPLAN conference on

Programming language design and implementation, pages 32-41, New York, NY,

USA, 2007. ACM Press.

- [30]

-

Wei Xu, Sandeep Bhatkar, and R. Sekar.

Taint-enhanced policy enforcement: A practical approach to defeat a

wide range of attacks.

In Security '06: Proceedings of the 15th USENIX Security

Symposium, pages 121-136, Berkeley, CA, August 2006. USENIX Association.

- [31]

-

Yves Younan, Wouter Joosen, and Frank Piessens.

A methodology for designing countermeasures against current and

future code injection attacks.

In IWIA 2005: Proceedings of the Third IEEE International

Information Assurance Workshop, College Park, Maryland, U.S.A., March 2005.

IEEE, IEEE Press.

Id: sqlia.tex,v 1.61 2008/10/13 13:32:18 dimitro Exp

Footnotes:

1http://cve.mitre.org/

2From now on we will often use the term

"query" to denote all SQL statements. Although SQL data

manipulation, definition, and control statements are not queries, using

the term "query" avoids confusion between the SQL statements

and the statements of the general purpose programming language where

SQL elements are often embedded.

3http://java.sun.com/products/jdbc/driverdesc.html

4http://www.us-cert.gov/

5http://secunia.com

6http://www.armorize.com

7Daffodil can be obtained from http://www.daffodildb.com/crm/

8The applications can be obtained

from http://www.gotocode.com/

9The

software is available at istlab.dmst.aueb.gr/~dimitro/sdriver